Main CPGW Record

Surname: ELSWORTH

Forename(s): Alfred Carr

Place of Birth: Barnoldswick, Yorkshire

Service No: M/10074

Rank: Senior Reserve Attendant

Regiment / Corps / Service: Royal Naval Auxiliary Sick Berth Reserve

Battalion / Unit: H.M.H.S. 'Rohilla'

Division: ---

Age: 31

Date of Death: 1914-10-30

Awards: ---

CWGC Grave / Memorial Reference: 8.

CWGC Cemetery: ---

CWGC Memorial: CHATHAM NAVAL MEMORIAL

Non-CWGC Burial: ---

Local War Memorial: BARNOLDSWICK, YORKSHIRE

Additional Information:

Alfred Carr Elsworth (born 3 November 1882) was the son of Albert and Mary Ann Elsworth, née Oldfield. Both parents were born at Barnoldswick, Yorkshire. Alfred was the cousin of Private Fred Whittaker (28621) (q.v.).

1891 Barnoldswick, Yorkshire Census: 15, Hill Street - Albert [sic] C. Elsworth, aged 8 years, born Barnoldswick, son of Albert and Mary A. Elsworth.

1901 Barnoldswick, Yorkshire Census: Cobden Street - Alfred Elsworth, aged 18 years, born Barnoldswick, son of Albert and Mary Ann Elsworth.

1911 Barnoldswick, Yorkshire Census: 32, Wellington Street - Alfred Elsworth, aged 28 years, born Barnoldswick, son of Albert and Mary Ann Elsworth.

A short biography of Alfred is included in: ‘Barnoldswick – A small Town’s part in conflicts 1800 to 2014’ by Peter Ian Thompson (2014).

See also:

‘Wreck of the Rohilla – Words and drawings’ by Ken Wilson (1981).

‘Into the Maelstrom – The Wreck of HMHS Rohilla’ by Colin Brittain (2014).

Data Source: Craven’s Part in the Great War - original CPGW book entry

View Entry in CPGW BookEntry in West Yorkshire Pioneer Illustrated War Record:

ELSWORTH, Alfred, 32, Wellington Street, [Barnoldswick], single.

The above resided at Barnoldswick, being a member of the local branch of the St. John Ambulance Association, who were drowned when the ‘Rohilla’, a hospital ship on which they were serving as members of the Naval Sick Berth Reserve, went ashore at Whitby on October 30, 1914.

---

Click the thumbnail below to view a larger image.

Senior Reserve Attendant Alfred Carr ELSWORTH

Regiment / Corps / Service Badge: Royal Naval Auxiliary Sick Berth Reserve

Data from Soldiers Died in the Great War 1914 - 1919 Records

Soldiers Died Data for Soldier Records

Surname:

Forename(s):

Born:

Residence:

Enlisted:

Number:

Rank:

Regiment:

Battalion:

Decorations:

Died Date:

Died How:

Theatre of War:

Notes:

Data from Commonwealth War Graves Commission Records

CWGC Data for Soldier Records

Surname: ELSWORTH

Forename(s): Alfred Carr

Country of Service: United Kingdom

Service Number: M/10074

Rank: Senior Reserve Attendant

Regiment: Royal Naval Auxiliary Sick Berth Reserve

Unit: H.M.H.S. "Rohilla"

Age: 31

Awards:

Died Date: 30/10/1914

Additional Information: Son of Albert and Mary Ann Elsworth, of 32, Wellington St., Barnoldswick, Yorks.

---

View Additional Image(s)

Additional Photo(s) For Soldier Records

View Craven Herald Articles

View Craven Herald Articles

06 November 1914

THE WRECK OF THE ‘ROHILLA’ OFF WHITBY – TWELVE BARNOLDSWICK AMBULANCE MEN DROWNED, THREE SAVED

A terrible tragedy of the sea was enacted last weekend on the East Coast off Whitby, when a splendidly appointed hospital ship of some 7,000 tons burden struck on submerged rocks while on its errand of mercy to the shores of France, and, within a half a mile of land, broke in two and was battered to pieces in the presence of thousands of helpless spectators. It was a tragedy in which the residents in the Skipton district generally, and of Barnoldswick in particular, took a very poignant interest, inasmuch as 15 ambulance men from the latter place – the majority married and with families – who were called up for service on the outbreak of hostilities in Belgium, were known to be aboard. At the time of writing only three were accounted for.

The Rohilla was a Glasgow steamer on her way from Leith to Dunkirk to bring soldiers from the Front. There were between 150 and 200 passengers on board, including a medical staff and five nurses. The disaster occurred at ten minutes to four on Friday morning last, at the height of a tremendous gale which raged in the North Sea and accentuated the dangers of navigation. Shortly after 3.30 a sentry on duty on the Pier Head at Whitby was astonished to see a large vessel loom up out of the darkness and pass silently within a few yards of the pier. Almost simultaneously a Coastguard sighted the vessel, saw her peril as she skirted the submerged rocks which stretch from the foot of the South Cliff, tried to attract her attention but failed, and the inevitable happened.

STRUCK WITH A GRINDING CRASH

Half a mile further on, within a few hundred yards of a curious promontory known as Saltwick Nab, the vessel struck the rocks with a grinding crash. In a few minutes rockets were sent up from the ship and answered from the Coastguard Station, from which the call to rescue was speedily sent forth. The town was soon aware that a large ship had gone ashore near their coast, and efforts were made to give prompt assistance.

The vessel seemed to be about 800 yards from the cliff and at the mercy of a furious sea, which pounded her on the rocks – admittedly about the most hopeless position for rescue that could be imagined on the Yorkshire coast. Numerous wrecks have occurred there, but few, within the memory of sailors with life long experience of that coast, where the obstacles in the way of rescue were so great. It was impossible to launch the larger of the two lifeboats from Whitby Harbour, or to drag it under the lee of the cliffs to a more favourable position, and all attempts on the part of the Rocket Brigade to establish communication proved fruitless.

A GRIM STRUGGLE BETWEEN HUMANITY AND ELEMENTS

A cheer went up from the crowd on the cliffs when a number of men were seen dragging the smaller of the two Whitby lifeboats along the beach towards Saltwick Nab, where, after a superhuman effort, a suitable place was found for a launch. While this was in progress, a shout from the watchers above drew attention to the fact that one of the Rohilla’s lifeboats had been successfully launched and was making for the shore. It was a grim struggle between humanity and the elements, but the boat came steadily on. Near the beach it was caught by a huge wave and tossed completely round, but eventually the little craft was grounded.

In it were the Rohilla’s second officer and five of the crew, and the rescue of the remainder seemed assured for the boat had brought with it a line from the steamer. To the dismay of all, however, the strain on the line was too great and it snapped before any use could be made of it. It now remained for the crew of the ‘ John Fielden’, Whitby’s smaller lifeboat, to make their effort. They immediately put to sea and after a great struggle, in which the issue often hung in the balance, the gallant fellows reached the Rohilla.

GALLANT WORK BY WHITBY LIFEBOAT

Thanks to the admirable seamanship of Coxswain Langlands, 17 of the survivors were taken off the wreck. These included the whole of the women on board – five in all – four of whom are nurses and one a stewardess. The boat made a safe return with its precious load and once again the lifeboat men returned to the fray. The second venture was equally successful, 18 of the Rohilla’s crew and staff being taken off.

Then for a second time the efforts of the brave rescuers received a cruel setback. In its double journey and rocky landings, the lifeboat had sustained such a battering as to render it un-seaworthy, and a third trip would have been courting disaster. Meanwhile, the Rohilla was suffering terribly from the seas. Prompt measures were taken to put the rocket apparatus into operation from the top of the Scar, and the local brigade were assisted by the men from Robin Hood’s Bay.

Rocket after rocket was dispatched, but the gale swept almost every line aside, the majority falling short. The failure of this apparatus was disheartening in the extreme, but the rescuers were undaunted. Word was sent to Upgang for the lifeboat to be sent from there and a period of waiting, terrible for those on the wreck and nerve wracking for the spectators on the cliffs, ensued. It was clear that the Rohilla was slowly breaking up, and about ten o’clock the stern, upon which a number of men still clung, was completely overwhelmed by an unusually large wave. When the smother of foam had passed by, the spectators saw that this part of the ship had turned turtle, and there was not the slightest trace of its former occupants.

LIFEBOAT LOWERED OVER CLIFFS

The bows were also settling down, and giving every indication of an early break-up. About an hour later the funnel fell away to seaward, and, after battering against the side of the ship for some time, sank out of sight. All who were left on board alive were now clustered on the bridge, the superstructure of the ship being alone above water. The bows had also broken away, leaving the central part of the boat standing like a small island in an angry sea, continually deluged by the waves.

News was now forthcoming that the Upgang lifeboat would shortly arrive. It had been dragged by men to within a mile and a half of Whitby, and was there met by six horses, pulled through the town, and up to the East Cliff. Then came the problem of getting it to the beach, some 250 feet below. The boat was dragged to the edge of the cliff and heavy ropes were attached, to which long lines of men hung while the craft was lowered bodily. After such exertions it was pitiable that nothing could be achieved, for, having got the boat safely beached, it was impossible to launch her. This seeming inactivity of the lifeboat men came in for some criticism on the part of many in the crowd, whose feelings were wrought by the awful helplessness of those who remained on the wreck. Meanwhile every attention was given to those who had been brought ashore, some of them half naked.

Throughout Friday afternoon the battered vessel – with its silent crowd clung amidships as the remnants of the vessel swayed to the impact of the sea and almost disappeared when a heavy wave broke over her – was watched by thousands of people. Capt. Neillson maintained his signalling, and by it the watchers learned that some on board were dead. Two men determined to reach shore by their own resources, they plunged into the breakers, almost naked, but wearing life-saving jackets, and, after much buffeting, were flung ashore, breathless and exhausted.

A NIGHT OF HORROR

Towards five o’clock darkness began to fall and the wreck took on the shape of a small, dimly compressed mass, in the centre of which a small yellow light shone with weird effect. In the midst of it all the Captain had managed to save an oil lantern with which he continued to signal ashore. Further bodies were recovered during the evening, and as the blackness of night descended on the scene it seemed as though nearly 100 souls must perish before the greyness of dawn.

With the ebbing tide came a lull in the storm, but it was deemed too hazardous to attempt to reach the wreck by lifeboat, and the rockets were a melancholy succession of failure. Shortly after eight the coastguards signalled suggesting that the surviving should try to reach the shore by rafts, to which the captain replied, “No thanks, prefer to wait until morning.” As the tide receded stretcher parties, with their ghostly lanterns, carried out their mournful task, crawling at the foot of the cliffs searching for bodies washed ashore. Of these there were by this time eleven, making 54 members of the crew accounted for. At midnight the survivors on the bridge were still keeping their dreadful vigil, and the yellow light was burning faintly.

MEN SWIM ASHORE

The break of dawn on Saturday revealed the superstructure of the Rohilla still there with its tragic human load. A courageous attempt was made to reach the survivors by the crew of the Upgang lifeboat, but it was impossible for the little craft to get near the wreck. Further failures by the rocket apparatus disheartened all, and when it was known that the Scarborough lifeboat, which had been standing off shore all through the night, could not get near, and that the Redcar motor lifeboat had broken down three miles out, the position appeared a desperate one.

Events now took a dramatic turn. From the ship came the semaphore message, ‘Prepare for men swimming’ and three men were seen to drop into the water. Two were powerful swimmers, and made splendid progress, but the third was carried further away, albeit all arrived safely. More and more men dropped from the wreck and volunteers to meet them in the heavy surf were plentiful. Some were semi-conscious, and there were many pitiable sights as the rescued were removed on stretchers made from wreckage.

As the day wore on the advance of the tide cut off the wreck, and rendered further attempts and swimming ashore impossible. Wreckage was continually being washed ashore and occasionally a body was found. Three were discovered west of the pier in the bay between Whitby and Sandsend – a mile and a half away from the Rohilla. Throughout the night searchers with lamps carried out their exhausting task at considerable risk. Nor did they search in vain. Four men were found alive and three dead. How many more had taken the plunge never to reach the shore, those on the cliffs – including many relatives of men known to have been on the ship – could only think of with a thrill of horror.

TEIGNMOUTH MOTOR LIFEBOAT TO THE RESCUE

The closing scenes of the tragedy were thrilling in the extreme. On Saturday night scarcely a flicker of hope seemed to remain, but soon after 10 o’clock a message was flashed to Capt. Neillson urging him to hold on until daybreak when help would be at hand. In the meantime the motor lifeboat from Teignmouth had promised to come down the coast during the night, and it was hoped that two or three trawlers would arrive in time, with a sufficient quantity of oil to break the force of the sea in the neighbourhood of the wreck, and thus enable the lifeboat to approach on the leeward side.

During the night it was noticed there was a lower note in the wind and the rush of the breaking foam was less ferocious. In the darkest hours that little group of shivering beings were greatly encouraged by the rays of an Army searchlight which reminded them that the watchers on shore were all at their posts.

At four o’clock the purr of a motor could be heard across the water. It heralded the arrival of the ‘Henry Vernon’ from Teignmouth, which had raced past the Harbour mouth, conveying to the sufferers the joyful news that she intended at daybreak to commence the work of rescue. After an exchange of signals with the Rohilla the motorboat entered the Harbour.

OIL POURED ON THE WATER

Dawn was just breaking when she crept out of the shelter of the piers, breasting the breakers bravely, and reaching the calmer water beyond the bar, heading for the wreck. Nearer and nearer she approached until no more than 200 yards separated the frail little craft from the remains of the Rohilla. Then she turned seaward, and some began to think she would never reach the object. Presently the lifeboat stopped and discharged gallons and gallons of oil over the boiling sea. The effect was remarkable; within a few seconds, as the oil spread over the surface of the water and was carried by the current towards the wreck, the waves appeared to flatten leaving a gently undulating sea in the region of the vessel. In the meantime the lifeboat turned about, raced at full speed outside the line of breakers, past the stern of the wreck, and then turned towards the shore. The most dangerous moment came when she was inside the surf and broadside on to the waves, but, guided with splendid skill and courage, she moved forward steadily, and a cheer of relief went out from the shore when she reached the lee of the wreck immediately beneath the crowded bridge. What were the feelings of those on board as they saw salvation at hand can only be imagined.

FIFTY SURVIVORS TAKEN OFF

But there was not a moment to be lost, for already the effects of the oil were beginning to pass off and the waves were noticeably higher. Quicker than thought a rope was let down on to the lifeboat, and immediately figures could be discerned scrambling down into the boat with a quickness and agility that seemed extraordinary in men one presumed to be exhausted almost to death. In less than a quarter of an hour more than 40 men had been taken into the boat.

It was then, while the rest were preparing to leave the wreck, that two enormous waves were seen rolling up from the sea at a tremendous speed. One after the other they swept over the bridge and across each end of the remnants of the deck on to the lifeboat at the other side, enveloping it fore and aft. Each time the tough little craft disappeared for a moment beneath the spray, re-appeared, tottered, and righted herself gamely.

Not a man was lost, not a splinter broken. Closer still she hugged the vessel’s side till every man aboard – 50 of them in all – had been hauled into the rescuing boat. The last man to leave his lost ship was the captain, and as he slipped into the lifeboat the crew of the latter gave a rousing cheer that was echoed again and again by the people ashore.

PATHETIC LANDING SCENES

In a short time the gallant little craft was safe in harbour and townspeople, having heard of the rescue, rushed with blankets, tea and other comforts for the rescued. Cheer after cheer rent the air as the boat neared the quay, and as the pathetic procession of survivors made its way up the steps both men and women were moved to tears. Not one was so utterly exhausted or badly hurt that he had to be carried up, but many tottered giddily, and all were pale and hollow eyed. Some bled from cuts, nearly all were barefooted and poorly clad, some only in pyjamas.

The captain seemed a man of iron. Unassisted he walked firmly up the steps, wearing his great overcoat and pince-nez, and looking as unperturbed as if he were returning from a pleasure trip. As soon as he reached the top of the quay he asked for a smoke, and then he stood quietly by watching the other survivors being hurried off after being given hot tea, to the Cottage Hospital, the Convent, and to private houses, where hospitality had been offered.

On Monday there was deep sadness in Whitby. Hundreds of relatives came from all parts of the kingdom to glean tidings of their loved ones, succoured from the wrecked hospital ship or lost in the sea, and one may not reveal the sorrow of despairing visits to a silent mortuary, where many of the dead are laid. To anxious and distressed visitors from afar, as well as to exhausted survivors from the wreck, the people of Whitby showed a hospitable and a tender regard.

THE ROLL OF HONOUR

The following is a list of the Barnoldswick men on board:–

Saved

Private W. Eastwood (married, two children), 8 Powell Street

Private Fred Riddiough (single), 13 Ribblesdale Terrace

Private Anthony Waterworth (single), North View Terrace

Missing or Dead

Sergeant Arthur Petty (married, one child), 2 Bracewell Street. Mr. Petty was secretary of the Barnoldswick Association

Corporal M. Birtwhistle (married, one child), 19 Clifford Street

Corporal W.J. Dalby (married, six children), 32 Westgate

Private H. Barter (married, no children), 41 Skipton Road

Private Tom Petty (married, three children), 11 Coronation Street

Private Tom Horsfield (married, seven children), 33 Heather View

Private Walter Horsfield (single), 7 Essex Street

Private Alfred Elsworth (single), 32 Wellington Street

Private J.T. Pickles (married, one child), Federation Street

Private H. Hodkinson (single), 14 Bank Street

Private W. Anderson (single), 20 School Terrace

Private T. Dunkley (married, one child), 9 Bairstow Street

THE TOWN IN MOURNING

The terrible disaster on the east coast has plunged the town into mourning. Since Friday last, when the first news was received from the two survivors, the centre of gravity in regard to the war has been transferred, for the moment at any rate, from the Continent to Yorkshire. Being a Red Cross ship the ill-fated ‘Rohilla’ cannot be disassociated from the war, which brought it into being, and though not directly a victim of the actual conflict it, along with twelve of Barnoldswick’s brave and devoted sons, has fallen a victim to the mightier and no less relentless forces of wind and wave.

When it became known that after the long vigil of Friday night the lifeboats had been unable to render assistance, a number of relatives and friends of the Barnoldswick men went through to Whitby by rail and motor car, others following on the Sunday, when the worst fears began to be entertained for the safety of the remainder. Eastwood was the only Barnoldswick representative rescued alive amongst those who had withstood the terrible fifty hours’ ordeal on the captain’s bridge. The circumstances of poor Barter’s death are most pathetic, he having made the attempt to swim ashore on Saturday and all but reached safety when he was dashed against the rocks by a wave, and killed.

The 15 Barnoldswick men were amongst those called up on the outbreak of war. They had only a short time previously returned from their annual training, several of them having been serving on men-of-war in Bantry Bay, Ireland. They were accorded a hearty send-off on their departure to headquarters at Chatham, whence the fifteen were drafted to northern waters for service on a hospital ship. During the intervening three months they have spent most of their time in the neighbourhood of the Scottish coast from Queensferry to the Orkneys. This was their first attempt to cross to the Continent, and there was a touch of irony in the fact that so many of them should meet their fate within sight of the coast of their own country.

As will be seen from the list, eight of those who have lost their lives were married men, two of them leaving large families. Most of them had devoted years of service to ambulance work, and had attained a high degree of proficiency.

Sergt. Petty was the secretary of the Barnoldswick Ambulance Brigade, and the services of Corpl. Birtwhistle were frequently invoked and freely given in accidents of a minor character. With two exceptions – Dunkley, a baker, and Barter, a railway goods porter – all the men were employed in the cotton manufacturing trade.

Mr. J. W. Thompson, gas and waterworks manager, who is the local superintendent, and has taken a deep interest in organising the Sick Berth Reserve, was naturally very much upset by the disaster. He went to Whitby on Sunday night, and was present at the inquest on Monday, when he put in a strong plea for the transference of any further bodies recovered to their own friends.

The body of Barter was taken on Tuesday to Worcester, where his father resides, for interment.

Feeling references to the sad event were made from most of the pulpits in the town on Sunday, and a public memorial service is being arranged for next Sunday at the Queen’s Hall.

The flags of the Conservative Club and the Liberal Club have flown at half-mast throughout the week.

A TERRIBLE NIGHT: PTE. RIDDIOUGH’S AWFUL EXPERIENCES

The following letter from Private F. Riddiough gives a graphic description of the terrible disaster. He states:–

Whitby, October 31st.

“I suppose you will have heard the news by now, but not quite all. We were sailing down the east coast bound for Dunkirk (France) on Thursday night. It was one of the roughest nights we have had since we have been away. The wind was blowing the ship wherever it wanted. We could not get to sleep all night. About 4 o’clock the following morning the ship shook from stem to stern. We all nipped out of bed. The water was pouring down the hatches in torrents. When I got out of bed I was ankle deep in water. I slipped on my pants and grabbed a life-belt and ran. When I got to the end of the line of bunks some bottles came dashing past and cut one of my toes clean off, all bar a bit of skin. I was walking about like that for four hours, so you can just imagine what I went through.

When I got upstairs into the saloon passage it was full of water and I was sent up against the wall. I then went up some more steps on to the promenade deck. No sooner had I got there than I was swept off my feet about three times, the waves coming mountains high. Then I got hold of a ventilator along with some other chaps, when a wave came and swept all of us off our feet right up against the rails. There I was in about three feet of water trying to get my wind! I got up and got behind a boat out of the way of the waves when I saw Tony (Pte. Anthony Waterworth) just beside me. We went forward and got into the Marconi chap’s cabin, where we stayed until daylight.

Then the ship’s doctor came and said we had better come out as it was not safe. We spied our chance (I was with Willie Anderson then; I had lost sight of Tony) – we waited until a big wave had gone by and then nipped forward into another cabin. Then I lost sight of Anderson, so I was on my own as far as our chaps were concerned. I stayed there about other hour and a half, when there was a lifeboat coming alongside, and the Captain shouted, ‘Women first!’.

As you know we had four sisters and a stewardess on board. Well, these got in and some more chaps, so I said to myself, ‘When that boat comes back I’m for it,’ so I climbed on to the rail and waited for it, and when it did come back I got hold of a rope and slid down into the lifeboat. A man pulled me in by the feet. When I looked up I saw Tony standing on the rail, so I threw the rope back to him and he came down into the boat.

I think we were the only two from Barnoldswick that got saved. I am now in the Cottage Hospital and am lucky to be here, I can tell you. I wouldn’t go through it again, not for a fortune. I think I shall be here for a while yet; then I shall get home on leave for a while.”

HOW PTE. BARTER LOST HIS LIFE.

From Mr. Harold Waterworth, who went to Whitby on Saturday to see his brother, and who returned home on Monday night, our representative was favoured with some interesting particulars of the wreck, and the rescue of the survivors on Sunday.

He arrived at Whitby by the 3-40 train. Mr. Waterworth found that his brother (Pte. Waterworth) had been ordered by telegram to report himself, along with some 35 others belonging the Naval Reserve and crew, at the headquarters at Chatham, so that he was only able to see him for a few minutes before his departure by the 3-55 train. He then proceeded to the mortuary to see if he could identify any of the bodies washed ashore, but could only recognise that of Pte. Harry Barter. The latter (Mr. Waterworth learnt) was one of those who had attempted to swim ashore, and had actually got within a few yards of safety when a big wave dashed him against the rocks and killed him.

“From what I could learn (our informant proceeded) only five of the Barnoldswick men reached the captain’s bridge – Riddiough, Eastwood, Barter, Waterworth and Anderson. Barter, Eastwood, and Anderson all made the attempt, along with another man named Moore, to swim ashore. Eastwood could not make any headway and was hauled back on to the wreck. Anderson was not seen again, and Moore was picked up dead.

Another survivor said when he was putting on his lifebelt after the vessel struck, he noticed several of the Barnoldswick men in the act of putting on their clothing when a big wave came and dashed in the side of the ship, knocking down the bunks on top of them, so that they had no chance of escape.

The scene on the beach on Saturday night baffled description. Bodies were being picked up almost battered to pieces, while those which retained a spark of life were in the most pitiable condition, some of them nearly black from head to foot. Only one amongst those whom Mr. Waterworth saw rescued alive was able to walk.

Eastwood, who was amongst those who had withstood the 50 hours buffeting on the wreck, was brought ashore on Sunday morning by the Teignmouth Motor Lifeboat. In a brief interview with our informant on Monday Eastwood said that not once during the whole agonising period did he hear anyone grumble about anything, nor even ask for either food or drink, knowing there was none to be had. The survivors did what they could to buoy each other up, and their heroic patience was rewarded. The Captain was the only one amongst the number of those rescued on Sunday able to walk up the steps of the jetty without assistance. Eastwood was able to recognise his friends who were so anxiously awaiting him on shore.

Mr. Waterworth was deeply impressed by the uniform kindness and sympathy of residents of Whitby, not only towards the rescued, but to their relatives. Indeed, there appeared to be quite a keen competition for the honour of gratuitously entertaining the survivors. One boarding-house proprietor, where Mr. Waterworth and four more visitors from Barnoldswick stayed, could not be induced to accept any remuneration.

A MELANCHOLY MESSAGE

Mr. J. W. Thompson yesterday (Thursday) telegraphed on Wednesday afternoon as follows:

Lifeboat has just returned from visiting the wreck. They didn’t find any bodies on it. The inside of the ship is washed out. Our eleven still missing. Divers have volunteered and will search the submerged parts of the ship tomorrow.

PUBLIC REFERENCES

At the monthly meeting of the Barnoldswick Urban District Council on Wednesday the Chairman said he could hardly allow the occasion to pass without saying a few words upon the sad fate that had overtaken the hospital ship and a number of their fellow townsmen. He thought the least they could do would be to pass a vote of sympathy and condolence with the families of the 12 men who had given their lives in the service of their country, and also to express admiration of their conduct. He believed they were all efficient in the class of work they had taken up, and it reflected credit upon the town that such men offered themselves for disinterested service. He moved accordingly.

Cr. Patten, in seconding, remarked that while their deaths were not directly attributable to the war, they were the outcome of it.

Cr. Jas. Edmondson, in supporting, said they were all men of sterling character, for whom everyone had a good word, and whom the town could ill afford to lose. Cr. Edmondson, from personal observations, spoke in terms of the highest praise of the overwhelming kindness of the Whitby people to the survivors and their friends from Barnoldswick, for which they refused any remuneration.

The motion was unanimously adopted.

Reference to the sad event was made at a meeting of the Brotherhood on Sunday afternoon, when Mr. John Heald, the chairman, said the Brotherhood, with which some of the men were connected, desired to express their deep sympathy to the relatives and families of the men who had sacrificed their lives whilst seeking to save the lives of others.

The Rev. E. Winnard, Baptist minister, also referred to the disaster, and the congregation signified their respect by the formal act of rising at the request of the pastor.

The young man Elsworth was a useful member of the Bethesda Baptist Church, and reference to this and to the sad event generally was made by the Rev. W. H. Lewis.

The Primitive Methodists have also been sufferers by the loss of members, and reference was also made to the event on Sunday.

A RELIEF FUND

It is said that the Naval Sick Berth Reserve being a comparatively new service, no fund for widows and orphans has been established, and we hear that efforts are being spoken of as likely to be made to assist the families of victims from the Prince of Wales’s Fund, or failing this, or in addition to this, the local Relief Fund. Dalby has left a widow and a family of half-a-dozen small children.

Mr. John Elsworth, of Barnoldswick, whilst walking on the beach at Whitby, picked up a small box bearing the name of his nephew, Pte. A. Elsworth, who is amongst those lost in the wreck. Amongst other odds and ends, the box contained a photo of his friend, Corpl. Dalby.

AN OFFER OF ASSISTANCE

Mr. Wm. Harrison, relieving officer, has received the following prompt offer of assistant to any of the dependents of the men from the Port of Hull Sailors’ Orphanage:–

To Mr. Wm. Harrison, relieving officer, Barnoldswick.

Port of Hull Sailors’ Orphanage,

November 4th, 1914.

“Dear Sir, – We are very sorry to hear of the loss you have sustained at Barnoldswick through the wrecking of the hospital ship Rohilla, and my Board last night instructed me to make inquiries in order to ascertain whether, in accordance with our rules, we could assist any of the cases. Will you kindly inform me as to their circumstances?”

JNO. W. DAY, Secretary.

SOME OF THE LOST

The two Horsfields amongst the missing were brothers, sons of Mr. James Horsfield, Essex Street. The elder (Tom) has been an enthusiastic worker in the Salvation Army. Pte. Dunkley was closely associated with the local branch of the Y.M.C.A., being the chairman of the committee up to leaving. The members extend their deepest sympathy to his wife and child.

A singular coincidence is related in connection with the wreck. On the night before it happened a child was registered at the office of the local registrar in the name of Hazel Rohilla, the latter name being adopted out of respect to the Barnoldiwick men who were known to be serving on board.

Pte. Walter Horsfield had two periods of service in the South African War, for which he received two medals. During the first period (April to October 1900) he was attached to No. 8 General Hospital at Bloemfontein, and the following year (January to August) to the General Hospital at Dielfontein.

13 November 1914

THE WRECK OF THE ROHILLA – IMPRESSIVE MEMORIAL SERVICE

At the Wesleyan Church on Sunday afternoon a united memorial service for the 12 victims of the above wreck was held, in which all the non-conformist bodies of the town were represented. A crowded congregation assembled, so great being the demand upon the seating capacity that an overflow meeting was deemed necessary in the adjoining schoolroom, which was also crowded. The ministers taking part were the Rev. M. Hall (Wesleyan), Rev. E. Winnard (Baptist), Rev. J. E. Woodfield (Primitive Methodist), Rev. W. H. Lewis (Baptist), and the Rev. R. Anderson (Congregational). Perhaps the most poignant moment in a memorable service was when the roll-call of the dead was called by Mr. J. W. Thompson (Superintendent of the local Ambulance Brigade).

Prior to the service a procession, headed by the Barnoldswick Brass Band playing the Dead March, was formed opposite the Gas Works, composed of over 100 ambulance men and nursing sisters, in uniform, representing contingents from Barnoldswick, Colne, Nelson, Foulridge and Earby. The service was opened by the singing of the hymn, ‘Oh God our help in ages past’, followed by a prayer by the Rev. E. Winnard and the rending of a portion of Scripture by Mr. Thos. Lane (Independent Methodist).

THE REV. J. E. WOODFIELD’S TRIBUTE

The Rev. J. E. Woodfield, speaking under stress of emotion, said if ever he felt the paucity of words or the limitations of the vocabulary it was at that moment, when they were met to express their feelings and sympathy as fellow townsmen and women in the great disaster which had overwhelmed them. Yet their tongues were totally unable to express all that was in their hearts. Never in all its history, he thought, had their little town been staggered by such a blow, or such a gloom been cast upon it as was caused by the news of last Friday week. Its effect was visible upon the face of every man, woman and child in their midst; sorrow was seen in every eye, and those apparently most immobile were touched to the very core.

The shock seemed to be made even greater by the reassuring news received early on that practically all their loved ones from Barnoldswick were among the saved, and if ever they realised the meaning of the adage that ‘hope deferred maketh the heart sick’ they knew it now. The question that trembled on every lip during those anxious days was ‘Is their any news?’ Snatching at the slightest crumb of comfort, and trying to buoy each other up with hope, anxious hearts alternated every hour between the two extremes of hope and fear.

THE STRONG BOND OF NATIONALITY

“We felt we would have given everything we possessed for good news; but our hopes have been shattered, our hearts saddened, and a darkness almost impenetrable has folded us in its embrace. I don’t want to say anything that will harass the feelings, or tear the wounds deeper than they are, for God himself knows the wounds are deep enough and will take a long time to heal. Yet it is our duty to pay our tribute to those who are gone and our sympathy with those left behind. We have a duty to those who have passed within the veil and to those on this side of it. We want to assure them today of our deep and heartfelt sympathy. In bigger towns, perhaps, the shock would not have been felt so keenly because more distributed. But here we knew and loved them all. Our hearts ache today for the dwellers in those homes where the shock and the blow have fallen the heaviest. We never realised before how our lives were interwoven; how our interests were bound up together. We realise now that the race is not a mere mass of distinct separate units just bundled up together, but that we are bound together by the strong bond of nationality and the sweeter bonds of love and affection.”

A ‘HEINOUS PRACTICE’

“We thought we knew something of the horrors of war, and our hearts have gone out in genuine sympathy to those who have suffered, but the horror and disaster of it had never come home to us in its awful significance as it has done since last Friday week. When the first paroxysm has passed away we shall know how to sympathise with those who have suffered.” Referring to the cause of the disaster, Mr. Woodfield said we learnt on Friday last that a different theory had been put forward by the captain, who said that the ship struck a mine, that he ran her ashore, and that had he not done so everyone aboard would have been lost. If that was so the wonder was not that so many were lost, but that so many were saved. Although that was neither the time nor the place to discuss methods of warfare, he would say that the sowing of mines was the most terrible method of all. It was futile to express the hope that in future this heinous practice would be prohibited, because their hope went much further – that this would be the end of all wars. Though proportionately their loss was greater than any other place in the list, he believed that everything that human skill and courage could suggest was done to save them, and today with their united breath they tendered thanks to those brave lifeboat men who in their anxiety to save took risks that had never been ventured upon before.

THE MESSAGE

What was the message this disaster spoke to us – ‘Be ye also ready.’ “We dare not close our eyes to their message.” (Mr. Woodfield went on.) “They have died heroes indeed. They have lost their lives whilst doing their duty. They have given their lives for their country and for us just as much as if they had been in the fighting line. Do not let us be unmindful of our duty. The path of duty is always the road to God, and they were treading it.” We were not all called upon to fight, nor to face the same dangers as they faced, but there were dangers facing every one of us. The danger of slackness or indifference was, he thought, the one which caused most people to drift on to the rocks. Thank God there was one strong enough to uphold the weak – Christ, who had himself sailed the stormy sea of humanity, and if the example of the brothers whose loss they mourned led them to put their trust in the Great Pilot, they would not have died in vain.

THE HEAVY TOLL OF DEATH

Rev. W. H. Lewis said they had been drawn together by the one touch of nature which makes the whole world kin. Their little town had been called upon to take its place with others throughout the land from whom a heavy toll of death had been exacted by the warlords of Europe.

Along the far-flung battlefront the stories of refugees flying in fear from their dismantled homes were fast becoming a commonplace of our daily lives. It was the sense of distance that made it impossible for us to realise all that was happening, and beyond the memory that such records existed they left the majority of us without any sensible or adequate appreciation of the grim horrors which other nations were daily witnessing. But when news was flashed into the town that this good ship had gone ashore off our own coast, and that the lives of 15 of their own townsmen were at stake, then it was that their imagination awoke and they felt that the real horror of war had been brought to their own doors in its grim and terrible nakedness. It was then they began to realise something of the pitiable tragedy that was being enacted in thousands of homes throughout Europe, and made their hearts go out today in sympathy that ran too deep for words.

AN APPEAL FROM NAMELESS GRAVES

Those who were bound by the ties of kinship and affection would find consolation in the thought that their loved ones had secured for themselves an honourable place among the grand succession of those to whom the world must ever remain debtors, and who could in sure confidence await the dawning of that day when the Master would say ‘In as much as ye did it unto one of the least of these ye did it also unto me.’ And while they paid their tribute of homage to the memory of the heroic dead, let them not forget the rich legacy they had left behind in the witness they bore to the cultivation of the greatest Christian virtues. It was only a little while ago since some of those present were receiving messages from some of these men – communications which they would now treasure as amongst life’s richest possessions. Today they were invited to stand and listen to the appeal they made to us from their nameless graves.

THE MINISTRY OF UNSELFISH LIVES

Witnesses to the homely virtue of mercy were doing their best to help to soothe, to heal and to comfort those who had been maimed in the far-flung battle line. Night and day they stood ready to answer the call to save those entrusted to their care; of them it could be truly said their mission was not to destroy but to save men’s lives. They were exponents of the great virtue of unselfishness. They were called to an intimate acquaintance with grief, and to accept conditions of life from which the more ease-loving would naturally shrink. It was not without cost to themselves that these men tore themselves away from the sheltering associations of home-ties and accepted the rigorous conditions under which they were compelled to live. Even in weariness they were ready to take their place beside the couch of the sufferer through the tedious hours of the day and the long vigils of the night. Theirs was the ministry of unselfish lives that counted the cost and accepted it. Had these men died in vain? Were they to be content to offer that poor tribute of a passing hour, and seek to perpetuate their memory only in that memorial service? From their grave they summoned us to emulate the example of kindness and unselfishness which they had left us. Let the men of Barnoldswick answer the appeal, for their placed must be filled. ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friend.’

Mr. J. W. Thompson then ascended the rostrum and the vast congregation soon rose while he called the roll of the departed. After the hymn ‘Jesus lover of my Soul’, and an earnest prayer from the Rev. R. Anderson, the organist gave an impressive rendering of the Dead March in ‘Saul’, and the service closed with the benediction, pronounced by the Rev. M. Hall.

Memorial services were also held on Sunday evening at the Primitive Methodist Church and at the Bethesda Baptist Church, with each of which several victims of the wreck were intimately connected. The former was conducted by the Rev. J. E. Woodfield, and the latter by Rev. W. H. Lewis. There were crowded congregations at both places of worship.

LETTERS OF CONDOLENCE

Mr. J. W. Thompson (Superintendent of the local Ambulance Brigade) has received the following from the Admiralty:–

November 4th 1914

Sir, – I desire on behalf of the Admiralty to express my deep regret at the loss of so many of your St. John Ambulance men in the wreck of the hospital ship ‘Rohilla’. These men have proved themselves to be of great value to our medical department, and their death is doubly to be regretted on that account. Could you kindly communicate my sincere sympathy to any dependents they may have had; theirs is a great sorrow, but it should be lightened by the thought that the men died nobly for their country.

I am sir, your obedient servant,

ARTHUR W. MAY

Medical Director General

Staff Surgeon R. W. G. Stewart (Inspecting Medical Officer to the R.N. Auxiliary Sick Berth Reserve) wrote as follows:–

Medical Department, Admiralty.

4th Nov., 1914.

Dear Mr. Thompson, – Will you please convey to the relatives of the members of the R.N. Auxiliary Sick Berth Reserve, who lost their lives through the wreck of the hospital ship ‘Rohilla’, my sincerest sympathy for the sad loss which they have sustained. I would also ask you to express to the members of the Barnoldswick Division St. John Ambulance Brigade my deep sorrow at the loss of so many brave fellows from this division. So far as I can learn at present I understand that only three of the members out of a total of 15 from your division who were serving in the ship have been saved.

Your men were a very great acquisition to the Reserve, well trained and disciplined, and knew their work and did it thoroughly. I have very pleasant recollections of the keenness of your men on the occasion of my annual inspection, and they will be a very great loss to the Navy. Might I ask you to let me know what temporary assistance the relatives and dependents are receiving until permanent arrangements are made.

With deepest sympathy.

Believe me, yours sincerely.

R.W.G. STEWART

Other letters have been received from the Southport, Accrington, Keighley, Silsden and Read Ambulance Divisions.

The sympathy of the Barnoldswick men at Frensham Camp (Surrey) was expressed in the following terms:–

Dear Sir, – It is with profound regret that we have learnt the sad news of the death of several members (whom we consider comrades) of the local branch of the St. John Ambulance in the wreck of the ill-fated ‘Rohilla’, and we beg to tender to you on behalf of the relatives of the deceased men our deepest sympathy in this their great loss.

We are, dear sir, yours faithfully, T. PATRICK, T. LANG, J. DERBYSHIRE, T. METCALFE, R. HUNTER, G. A. BRIDGE, C. LEIGH. (Privates of the 10th Battalion West Riding Regiment) on behalf of all men from Barnoldswick at this camp.

“Sincere sympathy with relatives of ‘Rohilla’s victims” was the message contained in a telegram from Barnoldswick Boys, Wool Camp, Dorset.

Colne and Settle Ambulance Divisions, and the following Barnoldswick members of the Sick Berth Reserve, now on active service at the Royal Sailors’ Home Hospital, Chatham:– W. A. Pearson, A. Starkie, J. D. Broughton, H. Holmes, B. H. Duxbury, H. Cobbold, J. Strickland and W. Lord.

THE THREE SURVIVORS

Mr. Thompson informs us that of the three Barnoldswick men rescued, two (Eastwood and Riddiough) are still in hospital at Whitby, both making satisfactory progress, and the third (A. Waterworth) has come home on leave for a week.

Up to the time of writing none of the bodies of Barnoldswick men have been recovered from the wreck, diving operations being impracticable owing to the turbulent state of the sea. Two bodies were washed ashore on Sunday, however, but they were those of other victims.

SUGGESTIONS FOR A PUBLIC MEMORIAL

A general meeting of the Barnoldswick Ambulance Brigade was held in the Drill Hall adjoining the gas works on Tuesday evening. Mr. J. W. Thompson (superintendent) presided. A vote of sympathy with the bereaved families was passed, and full acknowledgment made of the kind assistance rendered by the people of Whitby. It was also decided to send letters of acknowledgment to the several condolences received.

The question of making some provision for the bereaved families was discussed, but it was felt inopportune to take any definite steps until it had been ascertained what action the Admiralty were going to take. Mr. Thompson expressed the opinion that in the event of any public memorial being erected the most appropriate form it could take would be in the form of a drill hall, where the work could be continued under better conditions than hitherto. This view was fully endorsed. During the evening 49 new members were enrolled – 24 males and 25 females – making a total membership of 86. The number of names at present on the books as volunteers for active service is 39 – 25 males and 14 females.

The question of providing some suitable memorial to the dead heroes was also discussed at a joint meeting of the Barnoldswick Liberal Association and the Women’s Liberal Association on Tuesday evening. Mr. Stephen Pickles, C.C. (who presided) said the meeting had been called to consider what could be done to assist the bereaved families. The victims had lost their lives while engaged in the beneficent work of succouring the wounded when the vessel was wrecked, and it was their bounden duty as citizens of Barnoldswick to see that their families did not suffer in consequence. In the discussion which followed some uncertainty was expressed as to Government pensions. Cr. Harper expressed the opinion that the local relief fund would be available if applications were made, as also the funds of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association. He suggested, however, it would be better to wait until they had definite information as to what the Government were prepared to do.

The Chairman said the Member for the Division (Mr. Clough) might be able to render some assistance in that direction.

Mrs. Lever said there was another point. It was only right that the town should erect some memorial to the dead men, in order to show that they lost their lives whilst seeking to save the lives of others (hear, hear).

It was ultimately decided, on the motion of Mr. Waterworth, seconded by Mr. Heald, that the Urban Council be requested to take the initiative in organising a public fund for the relief of the needy families.

A vote of sympathy with the bereaved was unanimously adopted.

20 November 1914

BARNOLDSWICK – THE ROHILLA DISASTER

Mr. J. W. Thompson (superintendent of the Ambulance Brigade) has received the following expression of sympathy from Col. Sir Herbert C. Parrott, chief secretary of the Grand Priory of the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem in England:– “Let me take this opportunity of expressing the very great regret of the Earl of Plymouth and Central Executive of the Ambulance Department at the lamentable loss of so many members of your Division in the unfortunate wreck of the Rohilla. The only consolation is that they died for their King and Country, just as much as if they had been killed in the fighting line, but this does not diminish the great respect we feel for their memory, which will always be cherished in the Ambulance Department of the Order.”

L. G. B. INQUIRY

The ‘Rohilla’ Disaster – Mr. J. W. Thompson, superintendent of the local Ambulance Brigade, has received the following letter of condolence from Queensferry, Scotland:–

Queen Mary and Princess Christian Hospital, South Queensferry.

“Dear Sir, – Just a few lines on behalf of four members of the Earby Division of the Sick Berth Reserve who are stationed at the above hospital, expressing our sympathy to you all in your recent bereavement, by the wreck of the hospital ship ‘Rohilla’. We feel the loss very much, as we were the last persons who knew the twelve men from Barnoldswick to speak to them. We had them up here at the hospital only the day before they sailed away, and before they left we wished them the best of luck – but we are afraid it was ill luck. Besides, the ‘Rohilla’ was the ship which brought the last lot of patients here, and we have some of them here yet, and they all expressed their sympathy as they told us they had been well treated by the Sick Berth men on board. We hope you will kindly convey our sympathy to those in Barnoldswick who have so suddenly been plunged into sorrow.

“We are, yours sincerely, PTE. W. KAY, PTE. H. THORNTON, PTE. W. BRADSHAW, SERGT. E. SPEAK.”

Further bodies have been washed up at Sandsend, two miles to the north of Whitby, but they were in such a shocking state of decomposition as to be quite unrecognisable.

On Tuesday a coroner’s jury returned a verdict of ‘found drowned’, and assumed that the men had been drowned on October 30th, when the 'Rohilla' was wrecked.

On Tuesday the body of a seaman was washed up on the south beach at Scarborough, but the body was so decomposed that it was impossible to identify it. It was thought to be that of one of the crew of the hospital ship ‘Rohilla’. The body was quite naked, with the exception of a belt.

05 February 1915

THE ROHILLA FUND

Cr. Brown asked as to the outcome of the deputation appointed to meet representatives of the Conservative Club with regard to the proposal to establish a fund for the relief of dependents of the ‘Rohilla’ victims. The Conservatives were anxious to dispose of the money collected, he added.

The amount involved is about £11, which it was suggested some time ago should go to form the nucleus of a public fund to be vested in the Council.

Cr. Patten replied that he and Cr. Slater met the committee of the club and reported the result of the interview to the local Distress Committee as instructed. So far as he knew the latter had done nothing further in the matter.

The Clerk said the Distress Committee would meet this (Friday) night, when the question would very likely be brought forward.

Cr. Maude: “Did they make any recommendation?”

Cr. Patten: “No, we simply reported the position of things as we found them.”

02 April 1915

LOST IN THE ‘ROHILLA’ DISASTER

Sergeant Arthur Petty, Bracewell Street, married, one child.

Corporal M. Birtwhistle, 19 Clifford Street, married, one child.

Corporal W.J. Daly, 32 Westgate, married, six children.

Private H. Barter, 41 Skipton Road, married, no children.

Private Tom Petty, 11 Coronation Street, married, three children.

Private Tom Horsfield, 33 Heather View, married, seven children.

Private Walter Horsfield, 7 Essex Street, single.

Private Alfred Elsworth, 32 Wellington Street, single.

Private J.T. Pickles, Federation Street, married, one child.

Private H. Hodkinson, 14 Bank Street, single.

Private W. Anderson, 20 School Terrace, single.

Private T. Dunkley, 9 Bairstow Street, married, one child.

The above all resided at Barnoldswick, being members of the local branch of the St. John Ambulance Association, who were drowned when the 'Rohilla,' a hospital ship on which they were serving as member of the Naval Sick Berth Reserve, went ashore at Whitby.

15 June 1917

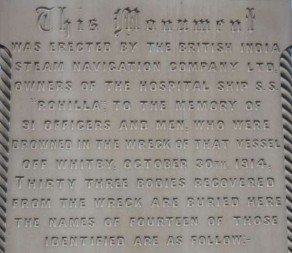

BARNOLDSWICK – A ‘ROHILLA’ MONUMENT AT WHITBY

A handsome stone monument has just been completed in Whitby Cemetery over the last resting-place of 33 of the victims of the ill-fated hospital ship Rohilla, in the wreck of which near Whitby on the 30th October, 1914, ninety-one officers and men (including twelve Naval Sick Berth attendants from Barnoldswick) lost their lives. The monument has been erected by Messrs. Thos. Hill and Sons, of Whitby, to the order of the British India Steam Navigation Co. (owners of the ‘Rohilla’) at a cost of over £200. From the ‘Whitby Gazette’ of last week (in which appears a photograph of the monument) we take the following description:–

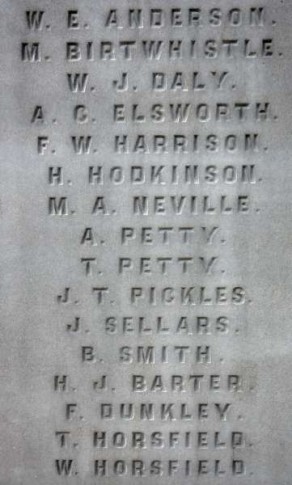

‘The monument is of the very best quality West Yorkshire stone, supplied by Messrs. Geo. Vint and Brothers, Idle, Bradford, and occupies a central position over the nine graves. The square monument stands 9ft 2incs. high, the dimensions at the base being 4ft. by 4ft. An ornamental anchor appropriately rests on the moulding towards the top of each of the four sides, while a ‘rope’ is effectively carved at each angle. The graves have been kerbed round and concreted and covered with broken marble. The names of the unfortunate victims have been engraved in the four sides of the monument; and the completion of the work reflects the highest credit upon all engaged in the erection of this handsome memorial.’

The names of the Barnoldswick men are inscribed (with others) on the east panel, as follows:– W.E. Anderson, M. Birtwhistle, W.J. Daly, A.C. Elsworth, H. Hodkinson, A. Petty, T. Petty, J.T. Pickles, H.J. Barter, F. Dunkley, T. Horsfield, W. Horsfield.

At the base of the front panel is the inscription:–

“I saw a new heaven and a new earth

And there was no more sea.”

View West Yorkshire Pioneer Articles

View West Yorkshire Pioneer Articles

07 August 1914

BARNOLDSWICK NEWS – LOCAL EFFECTS OF THE WAR

ick Berth Reservists Called up – The Naval Reservists Called up

Mr. J.W. Thompson, the local superintendent of the Royal Naval Sick Berth Reserve, first received warning of the likelihood of his men having to serve their country in a telegram he received on Sunday from the Chief of the First Aid Department, Chatham, stating that all men had to be in readiness to leave the town on short notice. The message was ratified by a further wire received from the same department on Monday morning saying that sixteen men had to leave at once for Chatham. The following men were chosen:– Corporal M. Birtwhistle [Birtwistle], Private T. Petty, Sergeant A. Petty, Privates T. Horsfield, W. Horsfield, A.C. Elsworth, J.T. Pickles, A. Waterworth, H. Hopkinson [Hodkinson], R.W. Eastwood, F. Reddihough, W.E. Anderson, Wilfred Lord, F. Durkley [Dunkley], H. Barter, and Corporal W.J. Daly.

The men were at once informed of their summons, and all presented themselves on the station platform for departure by the 12-8 p.m. train. The news of the summons had quickly spread, and a large crowd assembled on the platform to see them off, a crowd whose feelings were in strange comparison to those when the same train steamed out of the station a week before bound for Blackpool and Morecambe. People stood in small groups discussing the events, some, it is true, laughing and talking, but others realising the grave import of the summons and waiting anxiously for the Premier’s statement to be given in the House that afternoon.

The Departure

Prompt to the time the train whistle blew and the engine steamed out. A faint cheer was raised and a couple of detonators on the line served to emphasise the fact that if the worst come to the worst Barnoldswick would regard its first contingent of defenders with pride and welcome them back in more happy times. Here and there a woman was weeping, and even the more optimistic of the motley gathering had realised that their humour was ill-timed. Eagerly the train was watched down the line, and a farewell was bidden to Barnoldswick’s representatives 'at the front.’

06 November 1914

BARNOLDSWICK’S WEEK OF GLOOM – THE WRECK OF THE ROHILLA: THRILLING STORY

THREE OUT OF 15 LOCAL AMBULANCE MEN SAVED

This week has been one of the saddest that has ever been experienced by Barnoldswick people, for by the loss of the hospital ship, Rohilla, on the Whitby Coast, twelve gallant ambulance men out of fifteen who left the town on the outbreak of war have been lost. It is a sad story, but one, nevertheless, which will send a thrill of pride through succeeding generations when the story is related in years and years to come.

When war was announced these fifteen men, relinquishing their wives and families and all of them the comforts of home life, left home and joined the Royal Naval Auxiliary Sick Berth Reserve, being drafted to Chatham Naval Barracks. It is clear that subsequently they joined the Rohilla hospital shop, which plied between France and this country, carrying sick and wounded soldiers. The ship was making a return journey to France and struck a rock in Whitby Bay, 150 of the 229 souls on board being saved. Out of the fifteen Barnoldswick men on board only three were saved – a terrible low percentage.

Every now and again a dim light wagging hither and thither fitfully in the darkness indicates that they are still there, summoning feebly the assistance that those on shore cannot give.

THE STORY OF THE WRECK

The Rohilla was bound for Dunkirk, whence it was to bring British and Belgian wounded to this country. A full complement of doctors and ambulance workers were on board, including four female nurses, who are among the rescued. Exactly how she came to be so close in shore is not clear, but it is known that she passed within hailing distance of the pier head at four o’clock on Friday morning,

The sentry there tried to warn her, but his shouts were unheard, and ten minutes later she went aground under the cliffs. A very heavy sea was running, rain was falling in torrents, the night was pitch dark and a gale was blowing from the sea. The elements, in fact, seemed almost to have conspired for the Rohilla’s downfall, and from the first it was certain that a heavy death toll could not be avoided. Signals of distress brought the lifeboat crew and rocket brigade hurrying to the shore, but willing as the rescuers were, they could do nothing until the sea fell slightly with the arrival of daylight. By that time several bodies had been washed ashore. Although the storm had abated somewhat the waves were still running so high that it was impossible to take the lifeboat out of the harbour mouth, and with great difficulty it was dragged along the shore to a point opposite the wreck. In the meantime one of the Rohilla’s lifeboats, manned by the second officer and a crew of five, had come ashore with a line, but before communication could be established the line was broken by the force of the waves. All the remaining boats on the wreck had been either smashed or carried away, and the crew was powerless to make a second attempt. Two journeys were made to the wreck by the lifeboat, and two boatloads of nurses, stewards, and attendants were brought ashore. The lifeboat, however, was so badly battered that a third journey was impossible.

A second lifeboat was in the town, and as it was not possible to bring it along the shore, it was brought to the top of the cliff and lowered the two hundred odd feet down the almost perpendicular face of the cliff to the water – a feat probably unparalleled in the history of the Lifeboat Institute. Unfortunately when the boat had been lowered nothing could be done. The crew was anxious to man it and attempt the voyage, but it was realised that to do so would inevitably mean a further and useless waste of life. The Rohilla broke in two soon after she was struck, and at intervals during the day bodies were washed ashore.

MOTOR LIFEBOAT TO THE RESCUE

The last scene of this grim tragedy was a happy one. In the early hours of Sunday morning the fifty benumbed and starving people who still remained on board were rescued by a motor lifeboat, from Tynemouth, and were landed safely in Whitby harbour. Altogether, out of some 230 people who were on board when the Rohilla struck, 150 were saved alive. The rest were drowned or died from exposure. Many of the fifty people who were brought ashore on Sunday morning were in a pitiable condition. Clad only in their night attire, they had been exposed to the full fury of the elements since the ship struck, and they had had neither food nor drink to sustain them. Perched on the shoulder of one of them was a tiny wet bundle of fur, a kitten, sister to that which was brought off in the lifeboat on Friday.

THE NEWS IN BARNOLDSWICK

Our Barnoldswick representative writes:

By the loss of twelve lives out of the fifteen, which went from Barnoldswick to serve in an ambulance capacity upon the ill-fated hospital ship Rohilla, Barnoldswick as a town has this week suffered the greatest shock that the war has yet imposed. Local hardships caused by trade depression, anxieties about the welfare of loved ones serving their country in whatever capacity, could be born with fortitude, but the loss of twelve brave and well-known townspeople is a disaster that cannot so easily be overcome. It is only a short three months since the war began, and fifteen members of the Royal Naval Sick Berth Reserve left the town to take their part in the very necessary ambulance work, of which, alas, there has been plenty.

Of the fifteen men, only three, Privates Fred. Riddiough, Anthony Waterworth and W. Eastwood, have been saved alive from the wreck. The body of Private W. Barker was recovered dead, and all the rest are missing. It is presumed that they were drowned in the highest severity of the storm.

THE FIFTEEN

The Saved

Private W. Eastwood (married, two children), 8 Powell Street

Private Anthony Waterworth (single), North View Terrace

Private Fred Riddiough (single), 13 Ribblesdale Terrace

Missing or Dead

Sergeant Arthur Petty (married, one child), 2 Bracewell Street. Mr. Petty was secretary of the Barnoldswick Association

Corporal Birtwhistle (married, one child), 19 Clifford Street

Corporal W.J. Dalby [Daly] (married, six children), 32 Westgate

Private Tom Petty (married, three children), 11 Coronation Street

Private H. Barter (married, no children), 41 Skipton Road

Private Tom Horsfield (married, seven children), 33 Heath View

Private Walter Horsfield (single), 7 Essex Street

Private Alfred Elsworth (single), 32 Wellington Street

Private J.T. Pickles (married, one child), Federation Street

Private H. Hodkinson (single), 14 Bank Street

Private W. Anderson (single), 20 School Terrace

Private T.[F.] Dunkley (married, one child), 9 Bairstow Street

When the ship struck most of the Barnoldswick men were asleep, or trying to sleep, in their bunks. An interesting account of his experiences is given below by Private Fred Riddiough, one of the saved, in a letter to Barnoldswick, and these were similar to the experiences of Private Anthony Waterworth, who was taken away in the lifeboat at the same time as his companion. Private Riddiough’s account is given below.

PRIVATE FRED RIDDIOUGH’S EXPERIENCES

In a letter to Barnoldswick, dated October 31st, Private Fred Riddiough, who was one of the few Barnoldswick men saved from the wreck, gives a simple but comprehensive account of his personal experiences when the ship struck, and of the manner in which he made good his escape. He says:–

“We were sailing down the East Coast bound for Dunkirk in France, on Thursday night. It was one of the roughest nights we have had since we have been away. The wind was blowing the ship everywhere it wanted. We could not get to sleep. At about 4 o’clock the following morning the ship shook from stern to stern. We all ‘nipped’ out of bed, and the water was pouring down the hatches in torrents. When I got out of bed I was ankle deep in water, so I slipped into my pants and grabbed a lifebelt and ran. When I got to the end of the line of bunks some bottles came dashing past, and cut one of my toes clean off, all but a bit of skin, and I was walking about like that for about four hours, so you can just think what I went through. When I got upstairs into the saloon passage it was full of water. I then went up some more steps onto the promenade deck, and then onto the boat deck. No sooner had I got onto the boat deck then I was swept off my feet about three times, the waves coming mountain high. Then I got hold of a ventilator along with some other chaps, when a wave came and swept us all off our feet right up against the rails. Then I was in about three feet of water trying to get my wind. I got up and got behind a boat out of the way of the waves, when I saw Tony just behind me. We went forward to get into the Marconi chap’s cabin, and stayed there until daylight. The ship’s doctor then came and said we had better get out of there as it was not safe. We took our chance (I was with Willie Anderson then, I had lost sight of Tony), and waited till a big wave had gone by, and then we ‘nipped’ forward into another cabin. Then I lost sight of Anderson, so I was on my own so far as out chaps were concerned. Well, I stayed in there for another hour and a half. There was a lifeboat coming alongside, and the Captain shouted “Women first”. As you know, we had four Sisters and the stewards on board. Well, they got in with some more chaps, so I said to myself, “When that boat comes back I am for it”. So I got onto the rail and waited for it to come back, and when it did come, I got hold of a rope and slid down into the lifeboat. A man pulled me in by the feet. When I looked up I saw Tony standing on the rail, so I sent the rope back, and Tony got hold of it and came down into the boat as well. I think we were the only two from Barnoldswick to get saved. I am now at the Cottage Hospital, Whitby, and have just had some relatives to see me. I am lucky to be here, I can tell you. I would not go through it again for a fortune. I think I shall be here for a while yet, and then I hope to get home on leave. “

From this communication one may gather some idea of the terrible night of anxiety, and the days of peril that followed, for it was not until Sunday that all the saved were removed from the ship. From the time the ship was struck, 4 a.m. on Friday, every possible endeavour was made by the crew to obtain communication with the shore, and when daylight illuminated the awful scene, various attempts were made by the Whitby lifeboat men to reach the doomed vessel. As Mr. Riddiough states, the ladies were taken ashore in the first lifeboat, whilst a number of men, including himself and Waterworth, departed when a second visit was paid.

HOW BARNOLDSWICK RECEIVED THE NEWS

The first news to reach Barnoldswick of the disaster was by means of a telegram from Waterworth, stating that he and Riddiough were amongst the saved, and it was feared that they were the only two of the local men to have made good their escape. Consternation was everywhere felt, and at once telephonic communication was entered into regardless of expense, by anxious relatives and friends, all of whom were keenly desirous of learning the fate of the remainder of the local Sick Berth Reservists. Suspense was maintained all the evening. The only consolation that was to be gained was the news that many people were known to be clinging to the week, and that these might include more ‘Barlickers’. All the evening a crowd of people surged around the Post Office awaiting news that never came.

Already practical sympathy was being meted out to the relatives, and by the early train on Saturday morning a number of relatives left the town for the scene of the disaster. On Saturday and Sunday too, other people journeyed by rail, whist a number of local gentlemen kindly conveyed families by motor to Whitby.

On Saturday it became known that the dead body of Barter had been recovered, and later in the day came the welcome news that Eastwood had been saved. No more news regarding the fate of the Barnoldswick men was forthcoming, and on Wednesday morning the tale that had to be told was that only three of the local men had been rescued, that one body was recovered dead, and that the remainder were missing.

Throughout the week little bits of news had percolated from the scene of the disaster.

All the men, with the exception of H. Barter, who was a goods porter at the Midland Station, and T. Dunkley, a baker, were employed in the cotton trade. A story was circulated in the town regarding the fate of Barter. It is known that he was a good swimmer, and the report is that he essayed to swim ashore. After having been tossed about like a cork in the raging surf, the account is that he actually got his feet on land and had commenced to wade forward into safety when a huge wave dashed him backwards against some rocks, thus killing him before the rescuers, who rushed with ropes into the sea, could get near him. Barter was a Worcestershire man, and his wife, who left Barnoldswick during the weekend, has had his body conveyed to his native town, where it was interred, amidst local manifestations of sorrow and sympathy on Tuesday last. Mrs. Barter was staying with relatives in the south.

Lack of news regarding other Barnoldswick survivors extinguished the faint hopes that were held on Sunday and Monday for their safe recovery. Anxiety is still maintained regarding the recovery of the bodies.

NOT HOME YET

When the lifeboat landed Riddiough and Waterworth, they were taken to the Whitby Cottage Hospital, where they were visited by relatives and friends on Sunday. Eastwood was taken from the wreck by the Shields motor lifeboat upon its arrival. Various rumours have been circulated regarding the experiences of this survivor. One is to the effect that he jumped from the Rohilla into the sea, and was tossed back again by the huge wave, and another phase of the same story is that he attempted to swim to land, but was unable to make any headway in the raging storm, thus being assisted to regain the poor shelter and doubtful safety of the vessel itself. Whatever his actual experiences must have been, there can be no doubt that he has suffered terribly. He is at present detained at Whitby, where he has been seen by his brother, who went from Barnoldswick on Monday. Waterworth and Riddiough have been ordered to Chatham to report themselves upon recovery from shock and the injuries they sustained. It is probable that they will be permitted to return to Barnoldswick this weekend.

WATCHING FOR THE BODIES

No one has been more assiduous in seeking to alleviate suffering, arrange for the comfort of the survivors, and assist Barnoldswick people who have gone to Whitby, than Mr. J.W. Thompson, gas and water engineer, who is superintendent of the local Ambulance Division. Mr. Thompson got to Whitby on Monday, and at once wired to the Postmaster at Barnoldswick that none of the eleven bodies of the missing men had been recovered. In addition to giving evidence at the inquest, Mr. Thompson has kept Barnoldswick people posted with what news there was to send.

A telegram from him was placed in the window of the Post Office to the effect that ‘Divers have volunteered and will search the submerged parts of the ship tomorrow (Thursday). Lifeboat has just returned from visiting the wreck. They did not find any bodies on it. The inside of the ship is washed out. Our eleven still missing.’

Rev. Matthew Hall, who was a member of the motoring party to the East Coast, in an interview said that thanks to Mr. Thompson and the people in charge of affairs at Whitby, he was convinced that everything that possibly could be done had been done to reach and rescue the shipwrecked. He had seen the storm, hardly abated even then, sweeping the middle portion of the ship, which appeared to have struck the rock amidships. The bows and the stern had gone. What was once a beautiful and palatial vessel was now a complete shattered mess. The decks were swept clean, and the people of Whitby had gleaned flotsam and jetsam of all kinds after each tide. Some bodies had been washed up. But they did not include any of the Barnoldswick contingency. Mr. Hall said it was a pitiful sight. There seemed to be an abundance of lifebelts, and it was his impression that early in the storm the boxes that contained these valuable, almost priceless, instruments at such a time, were washed away from their lashings.

From the accounts Mr. Hall had received the experiences of Private Barter were terrible. It was especially lamentable that after making so brave and considerable endeavour to reach the shore, where he would have been on the point of rescue, only to be dashed against the rocks and tragically killed. By all accounts his body was terribly mutilated.

PERSONAL JOTTINGS

Most of the missing men have been associated with Barnoldswick Ambulance Brigade for many years, and have since served in the Royal Naval Sick Berth Reserve, taking part in the annual training ----- of H.M. ships. The two Horsfields were brothers, and sons of Mr. James Horsfield, of Essex Street, a well-known Barnoldswick gentleman. Mr. T. Horsfield was a member of an ambulance corps during the South African War. Mr. Milton Birtwhistle is a son-in-law of Mr. James Marsh, a well-known member of the Skipton Board of ----- and his services were usually required whenever an accident took place.

Sergt. Arthur Petty was one of the best-known St. John Ambulance workers in the town, and Mr. T. Petty was actively associated with the Salvation Army.

Messrs. Waterworth and Riddiough, who were saved from the wreck, had seen the least amount of service. They held a reputation, along with Eastwood, who was also saved, of being especially keen on -----.

A portion of the wreckage of the Rohilla has been sent to Barnoldswick, and is being made into a frame by Mr. J. -----. to contain the Ambulance certificate of Private Dunkley, and will be preserved by the relatives as a memento of the departed.

PULPIT REFERENCES.

In every place of worship on Sunday, prayers were offered for the safety of the shipwrecked men during the period of suspense. Reference to the sad event was made at the Brotherhood meeting on Sunday afternoon, when Mr. John Heald, the chairman, said the Brotherhood, with whom some of the men were connected, desired to express their deep sympathy with the relatives and families of the men, who had sacrificed their lives whilst seeking to save and preserve the lives of others. A vote of condolence was passed, the congregation standing the while.